Introduction

Measuring how much energy a fuel contains sounds simple: ignite it, capture the heat, and read a number. In practice, however, that process splits into several distinct methods, each tuned for different fuels, sample sizes, and accuracy targets. This article walks through the science and practice behind calorific value and heat measurement, explains common instruments and calculations, and shares practical tips from laboratory work and field testing.

Bomb calorimeter

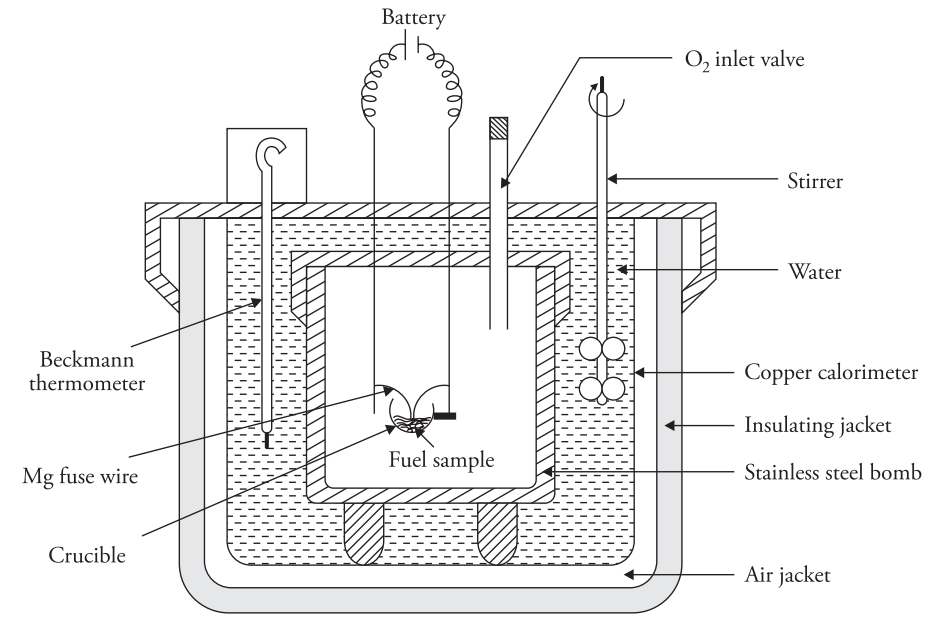

The bomb calorimeter is the classical tool for measuring gross calorific value of solid and liquid samples. A weighed sample is sealed in a robust container (the "bomb"), immersed in a known mass of water, and ignited electrically. The temperature rise in the bath, corrected for heat losses and calibration factors, yields the heat released by combustion.

Two main variants exist: adiabatic and isoperibol (constant temperature) bombs. Adiabatic designs try to eliminate heat exchange with the environment, tightening the measurement, while isoperibol instruments keep the calorimeter at a quasi-constant shell temperature and apply corrections. Modern instruments blend these ideas with electronic compensation to reduce operator error.

Principle of bomb calorimeter

- Stainless Steel Bomb: The stainless steel bomb is a cylindrical container with an airtight, screw-secured lid, two electrode holes, and an oxygen inlet. One electrode holds a ring supporting a crucible with the fuel and a magnesium wire. A platinum lining resists corrosion from acids formed during combustion. The bomb can withstand 25–50 atm pressure.

- Copper Calorimeter: You place the bomb in a copper calorimeter containing a known amount of water. The calorimeter includes an electrical stirrer and a Beckmann thermometer that measures temperature differences accurately up to 1/100th of a degree.

- Air Jacket and Water Jacket: An air jacket and a water jacket surround the copper calorimeter to prevent heat loss due to radiation.

Place 0.5–1 g of fuel in a crucible with a magnesium wire touching it. Add 10 mL distilled water in the bomb, seal it, fill with oxygen at 25 atm, and place in a water-filled copper calorimeter. Note the initial water temperature, ignite the fuel using a 6V battery, and record the maximum temperature reached. Measure the cooling time back to room temperature, then calculate the fuel’s gross calorific value using these readings.

Calculations

But

Corrections

2.Acid Correction:During combustion, sulphur and nitrogen in the fuel oxidise to form `H_2SO_4` and `HNO_3`.

Construction

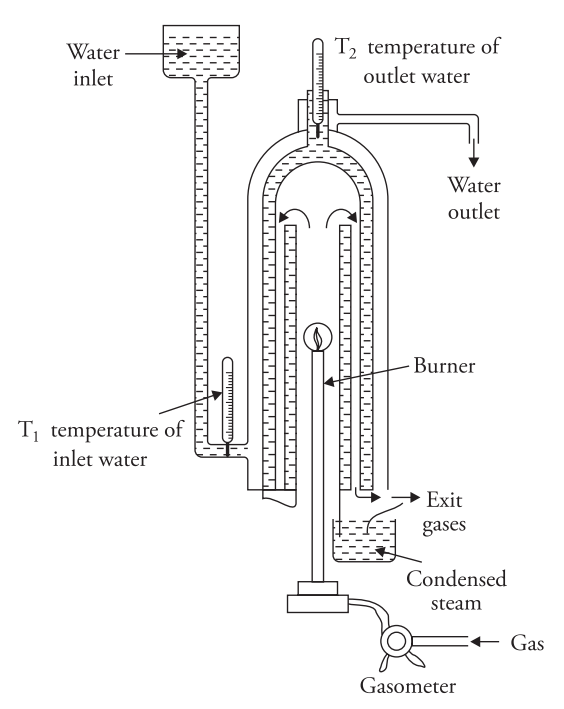

- Bunsen Burner: You use it to burn gaseous fuel. It clamps at the bottom, allowing you to pull it out or push it into the chamber during combustion.

- Gasometer: It measures the volume of the gas burning per unit time. A manometer with a thermometer attaches to it to record the gas pressure and temperature before burning.

- Pressure Governor: It regulates the supply of a gaseous fuel at constant pressure.

- Gas Calorimeter: This setup has a vertical cylindrical combustion chamber where you burn the gaseous fuel. An annular water space surrounds the chamber, allowing water to circulate and absorb heat. A chromium-plated outer jacket prevents heat loss by radiation and convection. The air within the outer jacket acts as an effective heat insulator. Openings at appropriate points allow you to place thermometers to measure the inlet and outlet water temperatures.

Observations

- The volume of gaseous fuel burnt at a given temperature and pressure

in a certain time = V`m^3` - Weight of water circulated through the coils in time t = W g

- Temperature of inlet water = `t_1` ºC

- Temperature of outlet water = `t_2` ºC

- Weight of steam condensed in time t in a graduated cylinder = m kg.

Let GCV of the fuel = H

V`m^3` of the fuel = m kg

= `frac{mtimes587}V` Kcal,

Boy’s Gas Calorimeter

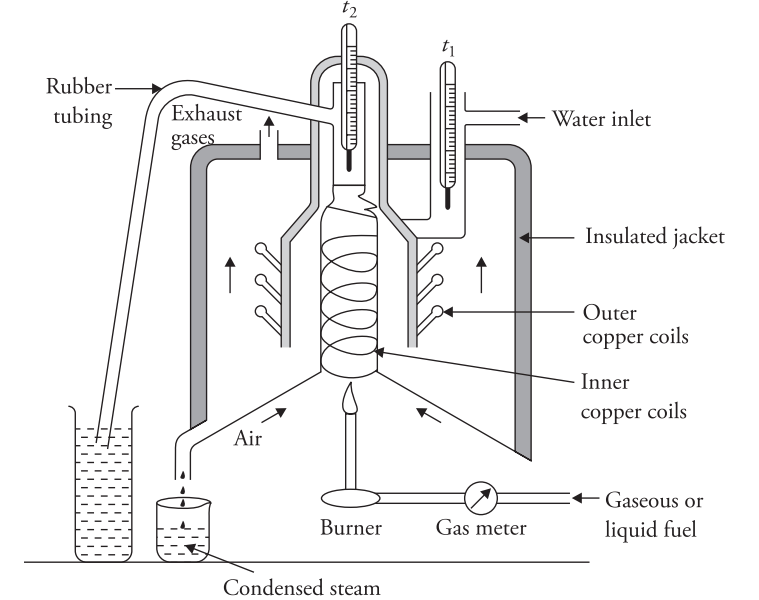

Boy’s gas calorimeter is a classic instrument designed specifically for determining the calorific value of gases. Rather than measuring energy per mass, it yields energy per unit volume of gas burned under controlled conditions.

The apparatus typically burns a measured volume of gas in a combustion chamber surrounded by a water jacket; the resulting rise in water temperature, corrected for losses, gives the energy transferred. Because gases are commonly billed by volume, this form of reporting remains practical and widely used.

- Gas Burner: You use a gas burner to combust a known volume of gas at a known pressure. A gasometer measures the volume of gas burned, while a pressure governor monitors the gas pressure.

- Combustion Chamber: The combustion chamber, or chimney, contains copper tubes coiled inside and outside it. Water circulates through these coils. It enters from the top of the outer coil, passes through the outer coils, moves to the bottom of the chimney, then flows upward through the inner coil, and exits from the top.

- Thermometers: Two thermometers t1 and t2 measure the temperatures of the incoming and outgoing water.

You place a graduated beaker at the bottom to collect the condensed steam produced during combustion.

Working Principle

Firstly, the working principle is like Junker’s calorimeter. Indeed, you circulate water and burn fuel to warm it for 15 minutes. Furthermore, once warm, adjust gas flow, consequently burning gas inside. Therefore, water absorbs heat, additionally circulating in tubes.Likewise, timing matters, accordingly record time t. Otherwise, errors occur. In fact, precise steps matter. Next, compare data, finally, refer to Junker’s calorimeter for calculations.

Moreover, heat transfer occurs,thus allowing measurement.Meanwhile,note water temperature rise,since it shows heat absorbed,hence aiding calculations. Similarly,measure gas volume burned, besides water volume circulated,ultimately using these for calorific value.Nevertheless,observe steam condensed; however,ensure accuracy.

For consistency, operators often dry the flue gas or measure its moisture content so they can report either gross or net calorific value. The presence of water vapor affects the heat recovered in the water circuit, so distinguishing between HHV and LHV is important for gas fuels.

Calibration, standards, and gas-specific issues

Boy’s calorimeters require calibration using a reference gas with a known calorific value or by electrical substitution methods where an electric heater supplies a known energy to produce a temperature rise equivalent to a test burn. Flow calibration for both the gas and the water streams is also essential.

Gaseous fuels can contain condensable hydrocarbons, water, and contaminants like H2S; these affect both the combustion process and the calorimetric measurement. Preconditioning the gas—drying or filtering when required—and measuring its composition helps produce reliable results and makes subsequent comparisons meaningful.

Conclusion

A thoughtful combination of bomb calorimetry for solids/liquids and Boy’s-style gas calorimetry for gaseous fuels covers most practical needs. With careful technique, consistent standards, and attention to the small corrections that matter, calorific value becomes a reliable parameter that engineers and scientists can use with confidence.